Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 12: LAND USE

THE ROAD [Laden Trail]

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH XIV – LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD

TAGS: Laden Trail or The Road ; prospectus ; map ; economic advantages of the Road ; hauling goods over the mountain ; cable incline ; Harlan County’s financial contribution ; high cost of road-building in Appalachia ; benefit to School’s endowment and scholarship fund ; fundraising for the Road ; Little Shepherd Trail ; Kentucky Good Roads Association Plan ; biodiversity ; Ethel de Long Zande; Katherine Pettit; Celia Cathcart; Evelyn K. Wells

LADEN TRAIL, or “THE ROAD,” is a historical record of the campaign for and the building of a paved road over Pine Mountain that would connect Pine Mountain Settlement School to the Laden railroad station near Putney some eight miles across Pine Mountain. Negotiations for the building of the Road began in 1914, approximately a year after Pine Mountain Settlement School was founded.

The close timing of the Road and the School’s beginnings was not coincidental. As construction of the School progressed, it became obvious that the steep Laden Trail — truly only a trail —over the mountain was inadequate for hauling needed supplies by wagon. By 1920 the founders of the School had a plan, had called in consultants and had begun a fundraising campaign for a road. This page features a map and their argument for “The Road” in a Prospectus that was written to inspire donations.

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD: Gallery

-

-

Prospectus: Road on Laden Trail across Pine Mountain. [delong_road_prosp_002.jpg]

-

-

Prospectus Map: Road on Laden Trail across Pine Mountain. [delong_road_pro_001.jpg]

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD: Transcription of the Prospectus

“Here, then is Appalachia: one of the great landlocked areas of the globe, more English than Britain itself, more American by blood than any other part of America, encompassed by a high-tension civilization, yet less affected by modern ideas, less cognizant of modern progress, than any other part of the English-speaking world.” — Horace Kephart

Will you help us build a road over our mountain, from Appalachia to modern America? The road will bring 5,000 people in touch with the railroad. It will be a wheeled-vehicle outlet for a great section of three mountain counties, which now have the most indirect communication with the world, either by costly, roundabout roads, or by tiny trails that even a sure-footed mule cannot haul a cart over.

It will mean economic improvement for the whole section — a market for apples and other surplus products — therefore, improved living conditions, larger houses, more knowledge of sanitation, a decrease in moonshining.

It will mean that the Pine Mountain Settlement School pays twenty-five cents a hundred pounds to haul goods from the railroad, instead of seventy cents. In 1916 the School paid to bring in from the L. and N. Railroad its groceries, building materials, heating apparatus, etc. $1000 of this, scholarships enough for eight children, could have been spent directly for their education, if there had been a road.

If we do not build the road, we will soon be at even greater expense in bringing in supplies. At present, we haul goods over the mountain on a broken-down cable incline, some eight miles away, built years ago to take poplar logs to the railroad. The cable sometimes breaks, the rails are rotten, and the incline is already dangerous. At the foot of the mountain, the goods must be reloaded onto wagons, and hauled eight miles over a road which is often impassable.

It is better economy for us to stop right now, and work for a road, than to go on spending money wastefully, year after year. It is also a more constructive policy for our neighborhood. Money spent now, in a lump, for the road, means improvement along many lines. Spent in smaller sums, year by year, it is frittered away, and accomplishes no solid good.

Harlan County cannot build this road now, because it is spending all it will have for some years on fifty or sixty miles of road in the heart of the county. Remember that road-building is in its infancy in Appalachia —that the hills and the creeks make a mile of good road a costly thing.

Our six miles of road are the costly link in a network of highways that will in time bind together three county seats, and give free communication to many square miles of mountains. For the passion for road-building has come to Eastern Kentucky. But a mountain a mile high, with seventy-five foot cliffs to blast through is a huge obstacle whose removal will hasten tenfold the opening up of communication, through the expenditure of County funds.

Harlan County has given five thousand dollars for this road,— a princely gift, — and the first large sum ever appropriated for the benefit of outlying districts. The county will also return $25,000 from its share of state road funds in annual installments of $1200 if we turn over to it the funds for road-building this summer.

The game is worth the candle, for the $25,000 will accomplish three purposes:

1. It will build the road immediately.

2. It will save the School money yearly, and thereby add to our

scholarship fund.

3. It will become endowment for the School as the annual installments are returned by the County.

Such results are worth a huge effort. A great constructive undertaking brings its own inspiration with it. $3500 has already been given for this project. For this $21,000 still needed we must find:

I. Givers of $500.

2. Givers of $100.

3. Friends who will organize groups to give $100.

4. Promoters, who will talk for the road, suggest possible givers, make appointments for Miss [Ethel] de Long, keep faith alive.

There must, and will be a road across Pine Mountain. How many feet of it will you help us build?

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD: History

What follows is a historical overview of the building “The Road” which was finally completed in 1940. The narrative concludes with a summary of the lessons that were learned and the changes the Road brought to the area and the School.

Laden Trail road, car and forested hillside. c. early 1940s [nace_II_album_086.jpg]

From Katherine Pettit regarding progress on the Laden Trail, c. 1920:

You’d be interested in the preliminary report Mr. Obenchain [State Engineer] has just gotten out. On this side of Pine Mountain, there is a rise of one foot in every 1.34 feet (less than 45 degrees). The distance through the mountain is 1-7/8 miles, but we shall need almost 12 miles of road at $6,000 a mile, with an ascent of five feet in every hundred feet. Some undertaking!

This note from Katherine Pettit to the board in the early 1920s was a preliminary assessment of conditions for a road across Pine Mountain to the School. It was among the first steps in the difficult task of bringing a road from the south side of Pine Mountain to the north side of the mountain or, more specifically, from the railroad station at Laden to the settlement school at Pine Mountain.

Geography is often confounding. In the eastern mountains of Kentucky, this is especially true. From the earliest records of exploration of the “Dark and Bloody Ground” of Kentucky to the present day, mountains have been a barrier, friend, wealth, an obstacle to progress, an insulator of culture, and just plain hard to negotiate. The early accounts of travel in the region speak to the tangle of laurel thickets, the sharp ridges and the undulating crests, the short distance but the long journey. Horses and oxen fared little better than their passengers and their loads teetered on slippery saddles or slippery slopes. On many mountain paths supplies slipped, people tumbled down hillsides, roots caught up the unwary and weather made all mountain travel unpredictable, dangerous and costly.

[lave015.jpg]

Katherine Pettit was wary of the rapidly developing industrial age, but she was practical and knew that if the school was to thrive it must have a viable transportation corridor for the exchange of goods, people, mail, and communication with new ideas. Rail had already been laid along the Cumberland river on the opposite side of the mountain to carry the cargo of coal and trees from the land, and this exploitative rush on the Southern Appalachians could not be stemmed.

Pettit and de Long believed that, while there were many reasons to join the industrial age, the process must be a partnership entered into with good skills and good sense, not one of exploitation. The isolation of the deep hollows and the mountain-locked valley would, in their view, eventually leave the region poor, exploited, and unhealthy. Roads, they believed, were part of the necessary infrastructure of the Progressive movement and they aimed to see to it that the school at Pine Mountain and the people of the long valley on the north side have this vital conduit to progress.

The undulating escarpment of the Pine Mountain, with its gentle dip slope and its sharp scarp slope is beautiful to view, but it yields few locations where roads can pass through natural gaps. The entire length of the Pine Mountain range, running northeast to southwest for 100 miles, give or take, is evidence of a thrust fault of major proportions. The settlement school sits at the foot of the steep side or scarp slope of the mountain.

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD: Biodiversity of Pine Mountain

A hike through the heavily forested area reveals the richness of the flora and fauna of the mountain. The Kentucky State Nature Preserves System has noted that there are more than 250 occurrences of 94 rare species of flora and fauna that are native to the region. Each year Pine Mountain School leads a walk through this wondrous mountain area that commemorates the early work of Emma Lucy Braun, a leading ecologist who stayed at Pine Mountain in 1916 while she conducted research on the “mixed mesophytic” (a term she coined) forest floor of the region. Her early work found the region to be the source of most of the woody species that appear throughout much of the Southern Appalachians. In the mesophytic forest there are some eighty different species as opposed to three or four in most other common forests. [Library of Congress: “Tending the Commons: Folklife and Landscape in Southern West Virginia: Cove Typography”, web resource]. Every year reveal the increasing risk to the some 250 occurrences of the 94 rare species of flora and fauna on the mountains surrounding Pine Mountain Settlement School.

‘Rebel’s Rock’ in early Spring, along the Laden Trail road, 2016. [P1120108.jpg]

It is through this wonderland of vegetation and long views that the workers and students walked to get to the School from the rail station at Laden (later Putney). As travelers came down the mountain from Incline (appropriately named) they could look northeast down the long valley and see

West Wind, the large white building that sits prominently on the hillside facing out from the campus. Many said that if they could see the building, they knew they were close to the school. But, it was still a long walk.

At $6,000 a mile and twelve long miles, the $72,000 road project was vastly beyond the fiscal grasp of the School, but not beyond a cooperative venture with the county and the state of Kentucky. Pine Mountain became the voice of the cooperative project and a long battle with bureaucracy and funding stretched over the course of many years and is well documented in the School records and archive. An important player in the construction was the Kentucky Good Roads Association.

KENTUCKY GOOD ROADS ASSOCIATION PLAN

In 1912 the Kentucky Good Roads Association came into being in order to promote better methods of road construction and maintenance and to improve the laws and under which the work on roads was to be executed. Out of these early discussions and over the course of about ten years the Kentucky Good Roads Association, a non-partisan association, advocated for the issuing of a $50,000,000 bond to be expended over a period of no less than five years in order to complete the state mandate of 1920 to construct a state-wide system. This system would connect every county seat with hard-surfaced roads. However, the Legislature of 1922 failed tp submit the bond referendum to the people in a timely manner and the Good Roads Association decided in 1923 they would push for the submission of the referendum in the 1924 Legislative session.

The Eastern Kentucky branch of the Kentucky Good Roads Association was formed in 1923 and joined with the Central Kentucky Good Roads Association. The two began a campaign for the adoption and passage of the referendum. Their adopted motto assigned by member Tom Wallace was “United, we move forward; divided, we stick in the mud.” This was in reference to the taxation for road repair that the people called the “mud tax.” The “mud” was a reminder of the condition of the many roads in the state that were in poor condition.

Various counties appointed district chairmen to represent them. Ominously, Harlan County had no representatives at the time the Kentucky Good Roads Association published their platform, which was to be taken to the State convention of the Good Roads Association in Lexington on July 19 and 20 of 1924. But, wisely, they were later chosen as a representative of Harlan County at the State convention. Pine Mountain was a voice in moving the Good Roads Association platform forward.

The plan of the 1923 campaign was to follow 3 objectives:

- Distribute literature and news matter in order to show the people of Kentucky what it would cost to build and maintain a completed system of hard surface roads.

- Form in every County an active organization to carry out the aims fo the Association.

- Through solicitation of memberships, collect fund to defray the expenses of the campaign, from every resident, taxpayer, person, firm or corporation having a legitimate interest in the construction of a hard road system in Kentucky.

The common practice of operating in a patchwork manner in which over 54 different centers of construction tried to coordinate jobs and plans, was not working and it was clear that the old patchy system needed replacement. Another challenge was found in what was referred to as the “Sinking Fund” which was the provision that was mandated to be used to pay off the bonds. The current funding for the Sinking Fund was also to be used to maintain the roads after construction. It was a sinking proposition. The ultimate outcome was a proposal that would require some $2,830,000 a year to retire the bonds in the timeframe mandated by the State agreement. With state revenues to off-set the pay-back, the total approximate maintenance budget could be kept at $1,100,000, a figure that some felt to be beyond reach.

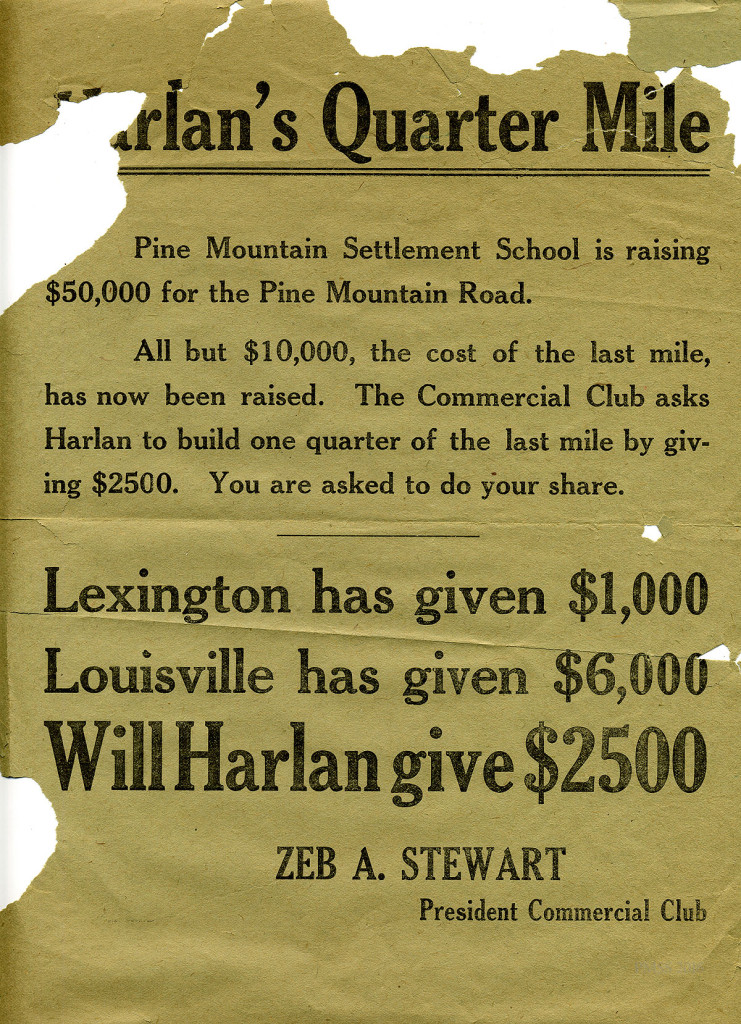

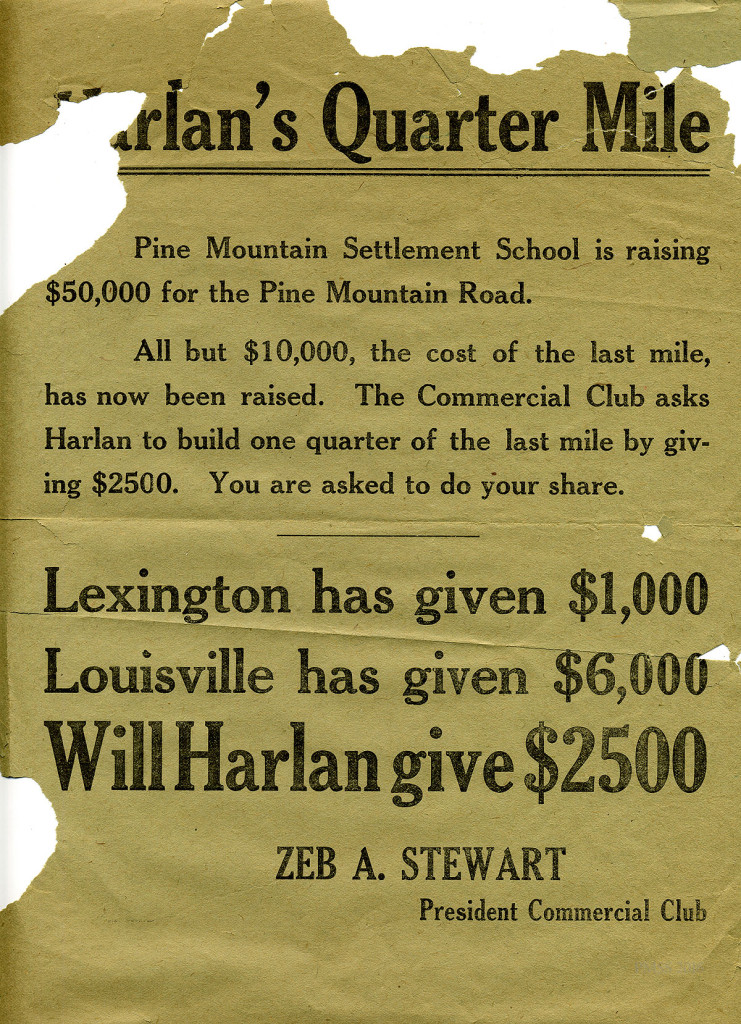

Broadside for the Pine Mountain Laden Trail Road project. [roads_004.jpg]

Katherine Pettit and others, like her, believed that many of the deficits claimed by the nay-sayers could be recovered by increased revenues to the counties through improved roads and increases in the motor traffic of the region. The assessment of motor vehicle owners, it was believed, could further offset the cost of principle and interest of the 30-year bond. The thirty-year cost would stand at around $85,729,721 which includes the principle of the bond of $50,000,000 and an interest rate of 4.5%. A further justification was made regarding the improvement that suggested the vital importance of roads to agriculture in the state and to the increase in opportunity for industrial materials transport.

The Kentucky Good Roads Association plan was a good one and one that had the full endorsement of the Pine Mountain Settlement School administration and staff, particularly the efforts of de Long and Pettit. Both Director Ethel de Long and Katherine Pettit saw the state referendum as an opportunity for the School to raise sufficient money to qualify for extension and improvement of the trail into a full and useful road from the Putney rail-head to the School. Though their efforts were not immediately evident, the trail would never have become a road had they not pushed for a corridor to transport goods and services into and out of the Pine Mountain valley. The trajectory of their effort was a long one, seen in the chronology below.

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD: A Chronology of Pine Mountain Settlement School Road History

A one-page document compiling the history of the “Road Over Pine Mountain” was drafted by an anonymous author. It captures the long course of events associated with the creation of Laden Trail Road by the School.

1913

The School asked Harlan County Fiscal Court to appropriate money for a good road over Pine Mountain. Early estimates placed the cost at $10,000, and in June the fiscal court appropriated half that sum, and the School started out to raise the other half.

Miss de Long made trips to Harlan, found the cost would be $50,000, instead of $10,000, [The] School was to raise half and the state give dollar for dollar. But [the] School had to raise the second half to loan the state which promised to pay it back in annual installments of $1200.

Miss Celia Cathcart went to work to raise the first half in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky. Miss de Long, from the School, raised the second half, which was to be the loan to the state.

Uncle William Creech went to Louisville to speak for the Road and made many friends for the School.

1918 – JANUARY

Surveying began after preliminary work done in 1915-1916.

1919 – May

Work began, but prices so high by this time that the Road had to cost $100,000. All the $50,000 raised by the School had to be used, and none of it would come back. In 1922 the funds gave out, and the Road had been graded only to the top of Pine Mountain [on the South side]. There was no money for further work on this [North] side.

Mrs. [de Long] Zande went to Frankfort to lobby, succeeded in getting a bill through which made the Road a link in the chain of State primary Highways between county seats, thus ensuring that eventually Kentucky would have to finish the Road. The School could do no more.

1924

The hauling road down this [North] side of the mountain was built by neighbors and county labor about 1924.

1929

In 1929 a sum of $50,000 was appropriated by the Harlan County Fiscal Court for the completion of the Road, and resurfacing of what had already been graded, but this sum was not available in the end.

1931-32

In 1931-32 the poor grade was improved a bit by the emergency relief workers. Aaron Creech was paid by the School to survey the new grade and was boarded at E.M. Nolen’s house free. Some work was commenced but was given up when the money ran out again.

1934

In the spring of 1934 the CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] workers began work on the new survey made by Aaron Creech. Right of way was given by all the owners except Otto Nolan, who has paid money by neighbors and School.

The Road was completed by CCC labor.

1937

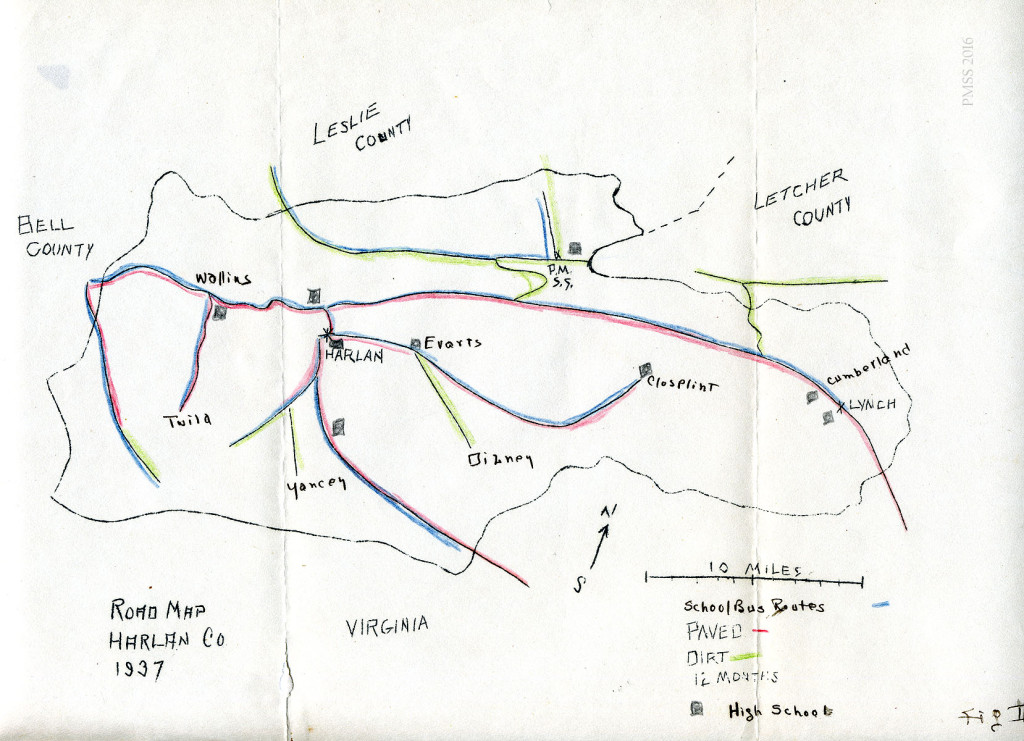

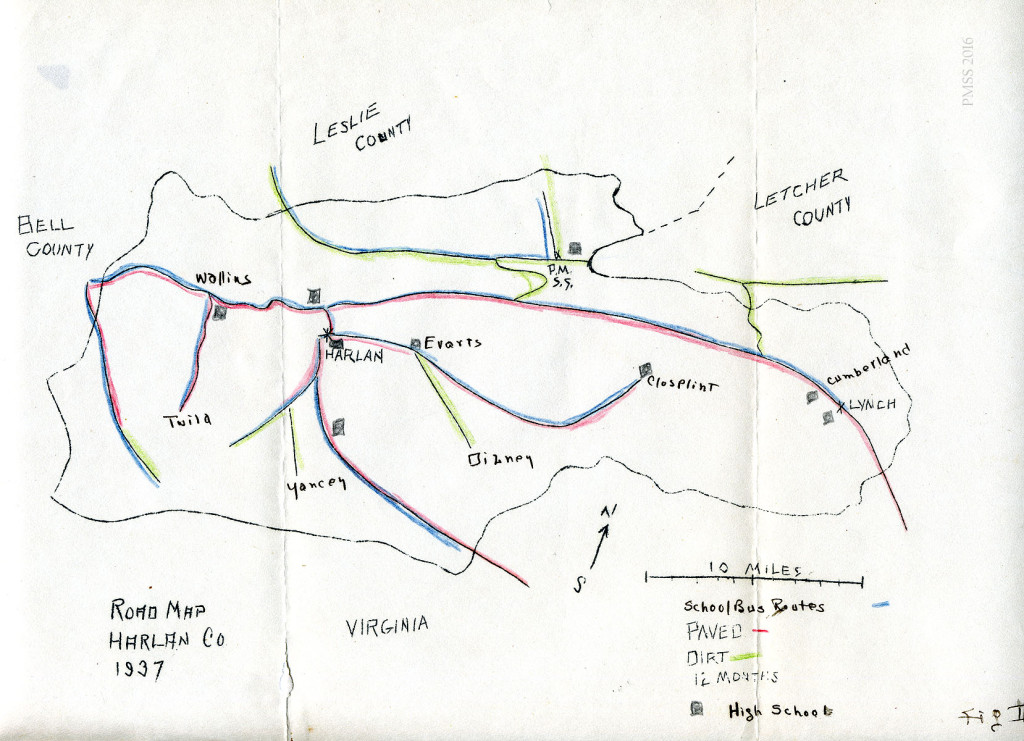

By 1937 the road situation in eastern Kentucky had improved and the number of paved roads can be seen in this hand-drawn map prepared by an unknown individual at Pine Mountain Settlement School. As can be seen in the map, the only high school that does not have access by a paved road is Pine Mountain Settlement School. While getting a road across the mountain was successful, access continued to be difficult for students on the north side of Pine Mountain. The “S” in green at the center top of the map is Laden Trail road as it leads into PMSS.

1937 Road Map of Harlan County, hand-drawn by anonymous individual and showing location of high schools in the county and their access by paved road in 1937. [roads_005.jpg]

Work on the Road continued for many years even after its energetic beginning. Evelyn Wells, the Editor[?], writing for the Pine Mountain NOTES in November of 1920, speaks lyrically of the progress on the Road :

The progress of the Pine Mountain Road has been without haste and without rest.

Six years ago we had a Dream of a Road.

Next year we hope to have The Road.

There is about its history a slow rhythm suggestive of classic Roman roads, which should augur well for its quality as a finished road. It started at the railroad, sauntering along so easily that one would never know it was climbing, stopping now and again at a refreshing spring or stream, or just to give one a chance to look at Big Black Mountain’s wonderful mass. It struck a little hill and had to gather up its young strength to eat its way through with a steam shovel that chewed out four hundred cubic yards of rock every day for weeks. Then it swept around the hill joyously and easily until it came to cliffs — a genuine jumping-off place, full of old bears’ dens. Here it halted many weeks while the air drills and steam shovels moved tons of rock to make a huge fill. And now the road continues its climbing unwearied, below the Rebel Rocks, through deep, still thickets of rhododendron, and across pure streams, viewing always the mountain across the valley. We stand at the point where the old trail crosses the road, and wonder if future visitors, coming across all the way on its beautiful, easy grade, will ever believe that once we all, two-footed and four-footed alike, scrambled up the twenty-five percent grade trail!

The other day at dusk, seven men started up the road on their mules, one behind the other, quite as if it were not wide enough for them to go three or four abreast. The Editor called out, “What makes you go up endwise still? Why don’t you ride together until you have to take the trail?” “We got so used to it we couldn’t help it” came the answer, and the Editor read again the poem of Mr. W. A. Bradley on the “Men of Harlan.”

“For, in that far, strange country, where the

men of Harlan dwell,

There are no roads at all, like ours, as we’ve

heard travelers tell.

But only narrow trails that wind along each

shallow creek,

Where the silence hangs so heavy you can hear

the leathers squeak,

And there no two can ride abreast, but each

alone must go,

Picking his way as best he may, with careful

steps and slow.”

Frances Lavender Album. I don’t know these girls but the rear horse is Bobby. — This is such a good view of our roads.

It was always a topic of conversation with workers and students as seen in this exchange in the student newsletter THE PINE CONE, October 1937, which captures the ambivalence of older staff to change and progress:

THEN

Signs of progress are the highways of travel

Asphalt, cement, sand and gravel;

All play a part in this building plan,

Making easy the tours of man;

Girding the earth like ribbons of gray

Stretch in untold miles the broad highway.

Mistaken the one who the above lines wrote,

The following facts are worthy of note

Pine Mountain, Kentucky, clings to the past

Old customs, old ballads, she holds these fast.

Highways of travel — roads did you say?

“No such animal” comes this way!

Trails, paths, a creek bed for a road

Rough and rocky — a light weight becomes a load;

Mud and slush, mire and hill —

Traveling her give one a thrill!

No easy sailing over a road like this;

End of journey is peaceful bliss.

Companions of travel along these bogs

Are countless razor backs and other kinds of hogs;

In spite of the primitive way of it all,

There’s something about it seems to call

To the soul of living for a bigger life,

Away from the modern rush and strife.

So here’s to Pine Mountain, her roads and her ways,

May the blessings of peace be hers always;

If progress and growth be her birthright

Grant these come with education’s light;

Roads — highways of hope!

These, too, perhaps in her horoscope.

AND NOW [The Editor (?) writes:]

The above poem, which was written by Miss McDavid, a housemother at Old Log in 1930, brings to the mind of a worker who has been away from Pine Mountain for seven years the great contrast between then and now. Change has taken place and it seems to be simultaneous with the building of the road. No longer is there a blind clinging to the past merely for the sake of tradition. The best of the past has been retained and many new things have been added. Old restrictions are gone. The freedom at Pine Mountain is an amazing thing, but more than that, the new responsibilities on the shoulders of each student are a sign of a large forward step. Roads are a symbol of civilization.

The ever-present question is in what direction will Pine Mountain go from now on? Has the road brought each student a new highway of hope?

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD: What About Today?

Today, in 2016, the School is encircled by paved roads and even roads that perhaps should have remained dirt thoroughfares, such as Little Shepherd Trail on the crest of Pine Mountain above the School. That one-lane scenic road was paved, in part, to keep it from washing out and, in part, as a response to the success of the paving of other scenic mountain roads, such as the Blue Ridge Parkway. However, the sections that are now paved will need to compete with foot traffic if a proposed Pine Mountain hiking corridor reaches fruition. Obviously, transportation corridors change and the changes reflect the changing times.

The lessons of “The Road” were many before it found its way across the mountain. The negotiation, cooperation, double-dealing, graft, community support, all brought along an education to a new generation entering the industrial age. The Road made the trip to the School easier for many visitors who made the journey. It enabled the Cooperative Store during the Boarding School year to function, and it kept the growing school supplied through the difficult years of World War II.

To put this simple unpaved road in perspective, the Appalachian Scenic Highway, later the Blue Ridge Parkway, was begun in 1935. The Parkway was a 469.1-mile road that stretched across two states and took 50 years to complete. The final Lynn Cove segment of the road was not completed until 1987!

The Road on Laden Trail, six miles of arduous negotiation and labor was finally completed in 1940. It is only in the late 1970s that the Road became a scenic route across the mountain. The completion of Highway 421 across Pine Mountain at Bledsoe became the preferred conduit for goods and people across the steep Pine Mountain ridge.

Today, Laden Trail is not a designated scenic parkway, but it holds a special place in the mind of the community and continues to offer the beauty of the forests of Pine Mountain and the long views of both the Black Mountain range on the south side and the peaceful Pine Mountain valley on the north side. It offers access to the Little Shepherd Trail, a popular narrow and scenic road that intersects the Laden Trail at near its mid-point. The Little Shepherd Trail, which runs along the crest of the Pine Mountain has become a long classroom for the many environmental programs that Pine Mountain School offers to the public.

Further, while the main transportation routes in the area are now paved, unfortunately, they remain some of the most dangerous roads in Kentucky and have some of the highest maintenance requirements. Due to the many years of travel by logging and coal trucks, the narrow roads in eastern Kentucky can be heart-stopping at times, and also confusingly un-marked and intricate.

Roads come with their benefits and their deficits, but it is certain that road construction leading into the Pine Mountain valley, one of the most remote of Harlan County’s areas, would not have happened for many years were it not for a passel of women working hard to pave the way.

SEE ALSO:

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD

LETTERS OF CORRESPONDENCE RELATED TO “THE ROAD”

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD CORRESPONDENCE Part I

LADEN TRAIL or THE ROAD CORRESPONDENCE Part II

CELIA CATHCART CORRESPONDENCE

LADEN TRAIL PHOTO GALLERY

LITTLE SHEPHERD TRAIL

LADEN TRAIL VIDEO (1980s) – Paul Hayes

![Judy Lewis, Community Coordinator and her GIANT teapot and equally large hospitality! [P1060589.jpg]](http://staging.pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/P1060589-e1433448094821-768x1024.jpg)

![005a P. Roettinger Album. "Country [?] Looking from Uncle John's toward the School."](http://staging.pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/roe_005a_mod-1024x769.jpg)