Pine Mountain Settlement School

Blog: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH V

FARM AND DAIRY II – THE MORRIS YEARS 1931-1941

ARRIVAL – LESSONS

108 Young boy and young Ayrshire calf.

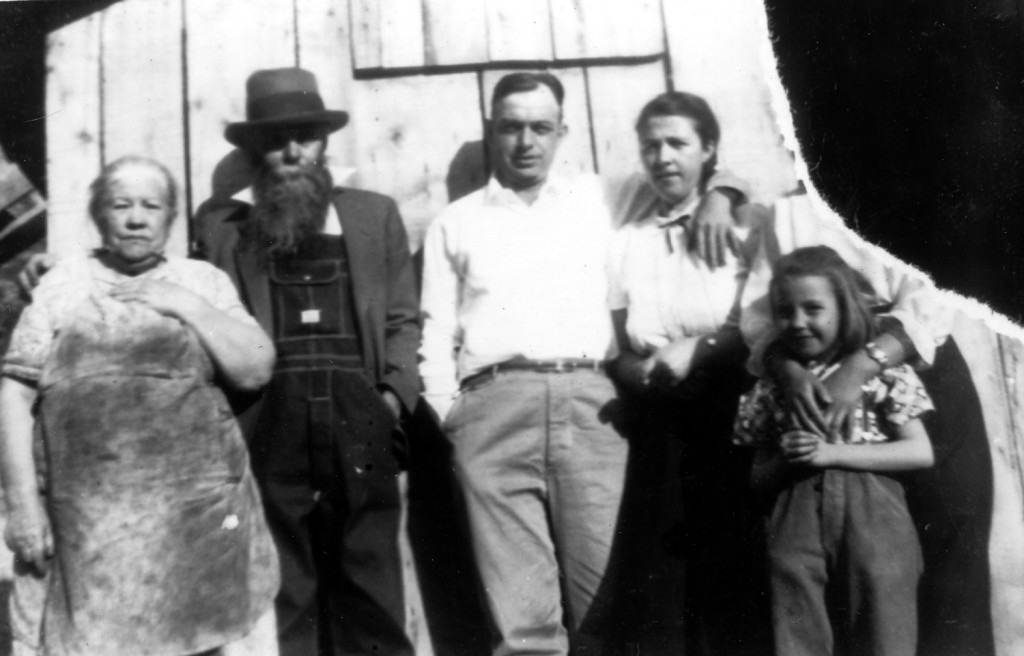

When Glyn Morris came to Pine Mountain as Director in 1931 he was just twenty-six years old and a recent graduate of Union Theological Seminary in New York City. The combination of theology and farming, while not new, took on a distinct character under Morris’ direction. When he arrived at Pine Mountain the environmental contrasts of urban and rural were stark, but Morris had been prepared. Born in the village of Glyn Ceiriog, North Wales, Glyn Morris was no stranger to rural life, nor to farming, as his family farmed and quarried the stones of the region. Morris was only four years old when he departed Wales with his parents for America. He was eight years old in 1913, the year Pine Mountain Settlement School was founded. When he arrived at Pine Mountain in 1931 he was 27 years old. His early years growing up on a farm were merged with his theological and educational training. He joined these skills with the pragmatic work of both farm and dairy already instituted at the School but not fully integrated into the curriculum.

In his autobiography Less Traveled Roads (1977) Morris describes his early years and the time he spent with his family first in Milford, Connecticut, then in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania where the Morris family joined a Welch community. In his book he describes the milk route he ran for a local dairy, his time at Albright College as a student counselor and a variety of other formative experiences, most notably as a camp counselor, paper boy, a steel mill jobber, and a master chorister. These many diverse experiences were brought into the mix of Pine Mountain and produced, through Morris, a remarkable experiment in education and in farming from 1931 until Morris’ departure from the school in 1942.

When Morris arrived to take on the Director role at Pine Mountains his youthful enthusiasm and his progressive educational views were not without their critics from the community as well as from the Board of Trustees. Over the years and following his departure to serve the war effort as an Army Chaplain in 1942, the tide of public opinion washed over him. When he returned to the School he was not fully endorsed by the Board of Trustees to continue his role at the School.

Criticism from the school’s Board of Trustees had been growing and several direct confrontations with members of the Board and with leaders in the community who had become increasingly conservative as the country’s involvement in the war grew, had caused him to re-think many of his fundamental values. Continuing with the School became increasingly difficult. Part of the growing local conservatism was in response to a growing resistance in the community to anyone who might stand in the way of the coal economy or who might have Socialist tendencies that would lend support to striking coal miners and advocate a Union. It Morris’ liberal political views that seemed to grate heavily against the increasingly conservative Board of Trustees of Pine Mountain. In fact, Morris had campaigned for Presidential candidate Norman Thomas, while Morris was a student at Union Theological Seminary. Thomas, a Socialist, was a settlement house worker and a pacifist. He ran six consecutive campaigns for President from 1928 forward , the year Morris supported him.

, the year Morris supported him.

In 1928 Thomas lost the election to Herbert Hoover and the Great Depression followed but Morris continued to pay homage to Thomas’ early path of pacifism and socialism and his early connection to the Social Gospel movement. As an articulate speaker, and as a Presbyterian minister, Thomas knew how to move his audience.He was a part of Morris’ early political and moral education and the residuals of this early education may be found in Morris’ first major conflict at the School as Director as described in his autobiography.

As Morris described the events in his autobiography, A Road Less Traveled, he tells us that the first year at the School he ran headlong into considerable local controversy in November of 1931 the year following the “Battle of Evarts,” a particularly deadly conflict between striking miners and local lawmen in the service of the local Coal Operator’s Association. New to the area, Morris did not yet have a grasp of the local politics and when he encountered a friend and classmate from Union Theological on the streets of Harlan he invited him to Pine Mountain. Arnold Johnson, a member of the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners (NCDPP) and after 1928 a member of the Communist Party, had been a classmate of Morris’ at Union Theological school and had joined the socialist movement that supported the growing unrest in the miner’s labor movement. In 1931 he was arrested in Harlan County for his union efforts and his “Socialist-Communist” views.

Later the IWW Committee led by Theodore Dreiser and including John dos Passos, Edmund Wilson, and others, came to the coalfields of southeastern Kentucky, where they observed and took testimony from coal miners striking in the Harlan County Coal Wars. Johnson’s trip pre-dates this famous group of reporters but he was seen as an enemy of the coal industry and was known to be a union organizer in a cou ty that was increasingly inclined to Union organization. The coal strikes of the early 1930s had left Harlan county fractured politically and the deep and growing fear of Union organizers promoted by the coal operators and the deep conservative antipathy toward any form of Socialism or Communism placed Morris in an awkward position with regard to his classmate, Johnson. Morris’ association with his theology classmate Johnson, soon brought him into conflict with the infamous J.H. Blair, sheriff of Harlan County, who supported the Coal Operators Association.

Morris was summoned by Sheriff Blair to come to his office and account for his activities and for his friendship with Johnson and his associates and to show proof that he was not a Socialist or a Communist. Given the dangerous and complicated events surrounding the mine-workers, it was remarkable that Morris made his case with Blair, but he did so with the assistance of workers at the School and the community of Pine Mountain. His community helped him to understand the gravity of his friendship with Johnson and any actions shown in support of the miners. Morris used this early experience as a reminder over the course of the next ten years when navigating the complex cultural climate in Harlan County as a Director and as a citizen of of the progressive School and the fast moving political climate.

FARMING AND MORRIS

By 1931, the year Glyn Morris arrived at the school as Director, the farm was a central part of the education program. But, nationally, farming was in trouble.

Nationally, farming, particularly tenant farming in the South was under siege, but it demonstrated a strength born of the land. Unionization was on the rise and it was integrated — a signal of the bonding aspects of working with the land and. Farm tenancy and sharecropping was not common in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky, but sharecroppers had long shared the other bond — poverty. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 was put forward to try to address the unbalanced privilege of large landholders. The Act soon prompted the formation of the Federal Farm Security Administration. While the FFSA was short-lived (abolished in 1946) it sent the right signals to small farms in its support of the small farmer and sharecroppers. Morris’s mentor, Norman Thomas, the Socialist organizer and graduate of Union Theological was instrumental in moving farmers toward a Union, but his greatest interest was with the unionization of miners associated with bituminous mining, the dominant industry in Harlan County in the early 1930s. The interests of the two men came together.

The Social Gospel had deep roots at Pine Mountain in the figure of Edward O. Guerrant, the influential minister and friend of the Pettit family. Norman Thomas’s foundation of rural settlement work, Social Gospel and Socialist leanings were shaped by the same mileu in which Morris was educated.

The political ties of Morris came with a deep appreciation for farming and a strong sense for land stewardship as well as social justice. These persuasions had their roots in his early childhood and youth experiences in Pennsylvania and his training at Union Theological. He understood what farming could mean for the educational and spiritual life of the school and the health of the community. He acknowledged and embraced the agrarianism of Katherine Pettit and William Creech. He began to build on their vision by adding his own knowledge of contemporary farming practice, community organization and scaled to the needs of the School to both political and social trends. Morris was a farmer, but he was first an educator, and obviously a increasing skilled politician.

STEWARDSHIP

Morris paid attention to the past and included the idea of stewardship in his educational package. In the earlier years the care of the school’s animals was everyone’s responsibility– a community endeavor. The health of these collaborative and critical food producers helped the school to maintain its costs and to support the educational programs of the school. Instruction in farm management was an early program at the School under Pettit and it was continued under Morris, albeit with refreshed agenda in the ten years of Morris’ tenure.

In the early days of the school the girls from Practice House [Country Cottage] were charged with caring for a school cow and for processing the milk for the other students and staff. It was this idea that caught the collaborative imagination of Morris and dairying quickly became a major part in his educational reform.

In his autobiography, Less Traveled Roads (1977), written at the end of his rich life, Morris recalls his first week at the school :

“My immediate focus of interest was the garden and dairy, particularly the garden, with its 5000 cabbage plants, rows of Kentucky Wonder beans, and large patches of Swiss chard, potatoes, turnips, onions lettuce radishes, corn, and other seasonal vegetables for the summer table — all of which, when stored or canned, would provide a substantial part of our menu during the ensuing school year. …” [Morris, Less Traveled …p. 49 ]

FARM AND THEOLOGY

At Union Theological Seminary Morris had concentrated his studies in a relatively new area of theology and education called “Church and Community.” It was a course of study more closely aligned with sociology than any other field of study offered at the institution and it included attention to rural farming practice. Steeped in the theology of Paul Tillich (1886-1965) , Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971), and the philosophy of Systematic Theology as expounded by William Adams Brown (1865–1943), the courses at Union prepared Morris well for the challenges of rural settlement life at Pine Mountain. The three influential professors at Union left their mark on Morris and subsequently on the school and agriculture at Pine Mountain. As described in his autobiography,Morris was enmeshed in the Seminary’s circles of influence and as a recent graduate he brought many of Union’s ideas to Pine Mountain. Soon he constructed a very progressive model for program management and for experiential education at the school. It would later prove to be a significant part of his legacy.

William Adams Brown, was an important idea generator for Morris. Brown, the son of a prominent banking family in New York City and was one of the founders of Union Settlement, an urban settlement house in East Harlem that worked with inner-city immigrants. Union Settlement was a progressive and well-run urban settlement house in the country’s largest city. But New York was not Eastern Kentucky. Testimony to Morris’ capacity to flex and a credit to his already rich lifetime experience, he crafted his rural knowledge with that of his urban mentors and with the other interns at Union Settlement and later Union Theological Seminary.

Brown’s influence was bolstered by the neo-orthodoxy of Reinhold Niebuhr and the existential theology of Paul Tillich, two other influencers. A remarkably effective blend of Union theology and philosophical education came together in the Morris vision for Pine Mountain Settlement School and its educational programs and is reflected throughout his direction of programs, including farming.

As a student at Union Morris chose the New York City Settlement House as his field-work experience. He was most likely instrumental along with his professors in getting an assignment as ‘Boy’s Worker’. In this position he was charged with the management of the day to day work assignments of the boys in the settlement. He wove into that daily experience the fundamental theology of Brown, who taught a course of study called Systematic Theology, focused on the core truths of Christian theology and the practical skills of work and not on the sectarian beliefs of any one religion or Biblical exegesis. Morris added to that pragmatism his own experiences growing up on a farm and in an industrial laborer family. Philosophically he took much from Brown’s much quoted book, Beliefs That Matter: A Theology for Laymen (1928) which was a foundational work for liberal theologians, particularly those who had attended Union Theological Seminary. Many of the Union Theological school graduates carried Brown’s ideas to core areas of social and theological practice in the United States. Morris’ classmate Myles Horton, founder of the Highlander Folk School, now in Newmarket, Tennessee was one of those who also pulled strongly from Brown and Niebuhr but the administration focus of the two was quite distinct. Horton was more closely aligned to social justice and civil rights issues while Morris administered more from the center and more integrated with current social and economic norms. In addition to Morris and his classmates, many later progressive leaders, such as Martin Luther King and others kept Brown’s systematic theology in the foreground of their life-practice and many helped shape critical civil rights reform in the country. While his community at Pine Mountain did not include individuals of color, Morris, was equally committed to raising up the people of the Central Appalachians.

BARNYARDS

So, what do theology and philosophy have to do with cows? As seen in the writing of both Elizabeth Hench and Glyn Morris — considerable. Morris believed that theology and philosophy were companions in the barn and on the farm and his progressive approach found many sympathizers and advocates in the staff, students, and for many years, the community at large. Today this agrarian theology and philosophy, so much a part of the Jeffersonian administration, still enters our farm language and lurks in our politics, as in the recent farm metaphor by a former Majority Leader of the House

I don’t want to leave my successor a dirty barn, … I want to clean the barn up a little bit before the next person gets there.” [Boehner, John CBS’s Face the Nation, Sept. 27, 2015]

Those delegated to cleaning of the barn, monitoring the yard, minding the gates and styles, and keeping a watchful eye on all those animals whose home was the barn and the yard, gave many students the discipline to monitor and master other corners of their lives and interactions. The farm hardened the delicate and softened the braggard.

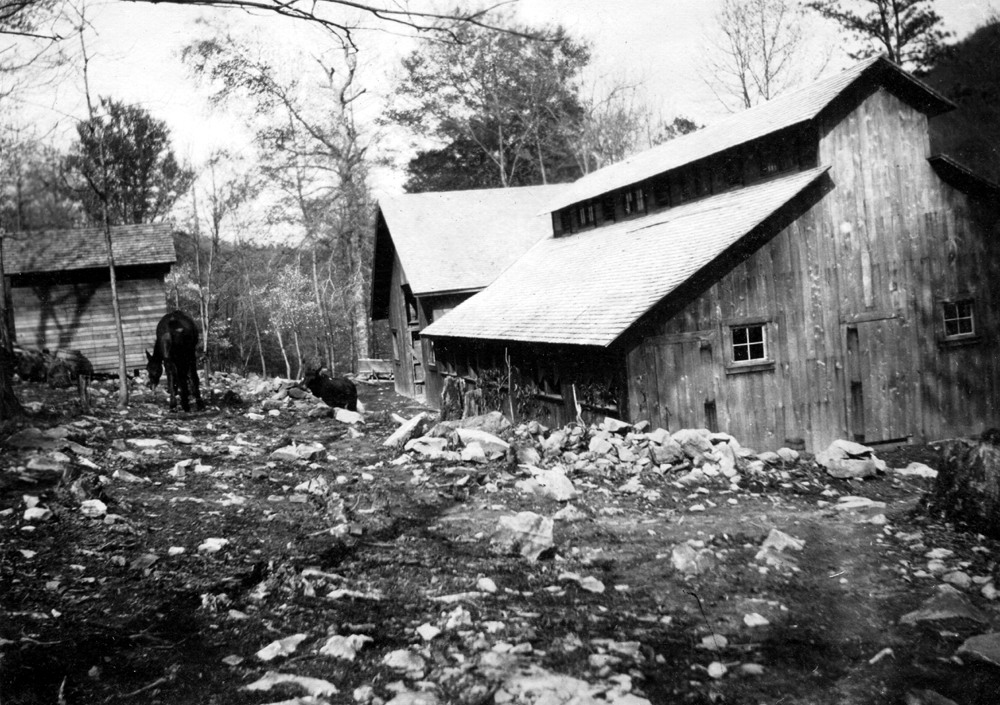

Barn. Early construction. Yard before stone collection and removal.

FARM AND THE PINE MOUNTAIN GUIDANCE INSTITUTE

The innovative ideas generated by Morris and his staff during the Boarding High School years soon received national attention. It is not overreaching to say that Pine Mountain had a lasting influence on farming and on education in the region. Lessons learned from Pine Mountain continue to inspire educators and school counselors in the region and even today as schools struggle to educate in a rough sea of social issues the hands-on model of Pine Mountain still rings true. Farm training, the co-op and classes in civics played significant roles in the educational models used at the School. The Rural Youth Guidance Institute, instituted by Morris at Pine Mountain in his last three years at the settlement school was a model of institutional cooperation. Inspired by John Brewer’s Education as Guidance: An Examination Of The Possibilities of a Curriculum In Terms Of Life Activities, (1932) and O. Latham Hatcher’s work with The Southern Women’s Educational Alliance, later called Alliance for Rural Youth, Morris established the Pine Mountain Institute. The stated purpose as outlined in the institute handbook was “to increase our efficiency in helping Harlan County youth to find themselves; by surveying their needs and all possible resources for meeting those needs; by coordinating these resources in a concerted effort to accomplish the above objectives.” This cooperative guidance for regional schools lasted for three years and spawned a series of Rural Youth Guidance Institutes. In just three short years, it garnered national attention and several publications by Morris and by the noted Columbia University educator, Ruth Strang, who often served as a mentor and speaker for Morris’ Institute. The Morris initiated Pine Mountain Guidance Institute was continued after his departure from the School to join the ranks of men serving in WWII by the Harlan County School system.

After Morris left Pine Mountain to join the war effort in 1942 as a U.S. Army Chaplain, a modified Institute was continued under the guidance of Harlan County School System Superintendent James Cawood in Harlan. The collaborative training conference was very pro-active in the reform of the local county schools. It is not surprising to find that the Pine Mountain Institute’s youth round table, a central part of the conference, was one of the earliest instances of racial integration in rural school initiatives. Black and white students sat around the same table trying to address local social issues long before those discussions finally brought integration to rural Southern classrooms. Jobs training, or industrial training and farming was always a part of the discussion.

John Brewer (1877-1950), one of Morris’ mentors, was a pioneer in the vocational guidance and counseling field but it was O. Latham Hatcher who gave Morris the connections he needed to move forward with the Pine Mountain Institute and who made the important connections between rural sociology and a pragmatic education such as farming. The well-known educator and former head of the Southern Woman’s Educational Alliance was seventy years old when Morris first met her. O. Latham Hatcher was feisty. She carried a dynamic personality that comes across in her correspondence with Morris.

O. LATHAM HATCHER, MORRIS, LITERACY, COOPERATIVES, ARTS AND FARMING

Literacy, international education, the arts, theater, cooperative economics and mathematics, home economics, and farming and stewardship of the land were all a part of Hatcher’s interests and her interests paired well with Morris’. The two merged their visions and their interests found their way into the integrated curriculum at Pine Mountain. It was a Progressive curriculum in the model of John Dewey but one that was well suited to the needs of the Settlement School and its service region.

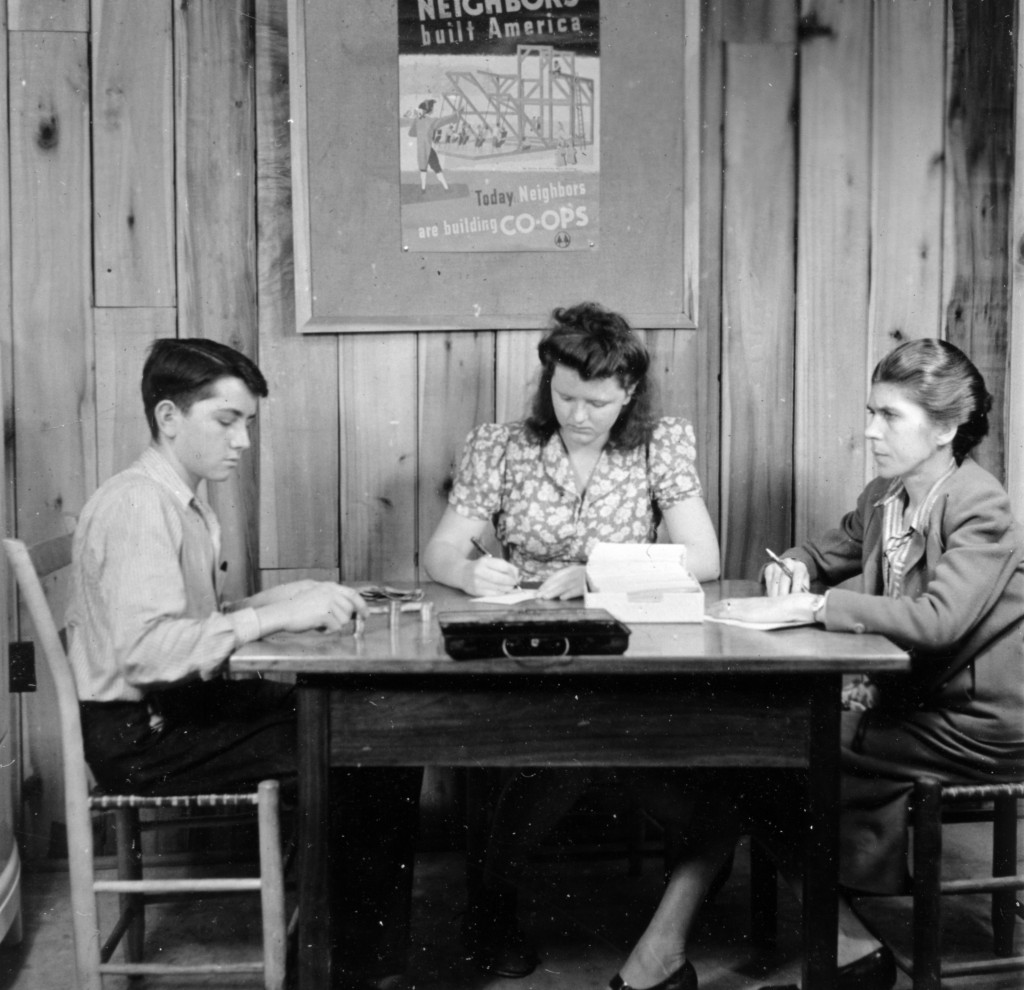

For example, a program which combined the expertise of teacher Angela Melville and her interest in cooperatives, the entire tenth grade in the late 1930’s was built around the theme of cooperation. This cooperation found a solid model in the idea of a “co-op” and the management by students of a Co-op store. The idea spread and later became a model for local farmers in the valley who were looking for a means to market their produce.

The eleventh grade curriculum focused on field-work in the community and the students participated in formal study of Folkways as well as engaging in pragmatic tasks such as home-repair and Pack-Horse libraries. While no grades were given for any of their courses, students were accepted at both Berea and the University of Kentucky. Their acceptance was based on the recommendations of Pine Mountain staff and the extensive portfolio of work, progress reports and recommendations maintained by the school for each student. Often these portfolios ran from 50 -100 pages of close observation by classroom and industrial instructors as well as housemothers and advisers.

Gladys Hill (right) with co-op students. (Source: Harmon Fdn stills)

The twelfth grade students were given college preparatory coursework if that was their desire and their aptitude and their courses in their final year were singularly academic in nature. It was an innovative curriculum that paved the way for able students to continue their work in college if they chose to do so or chart a course for industrial work. For those students who were not inclined to college work, there were skills training classes and trade preparation such as mechanics, printmaking, dairying, and other farm skills.

College work was not the required outcome for students at Pine Mountain but it was rigorous enough to garner approval by the state of Kentucky. During the Morris years the school was accredited by the State Department of Education based on an elaborate system of accountability for all areas of learning.

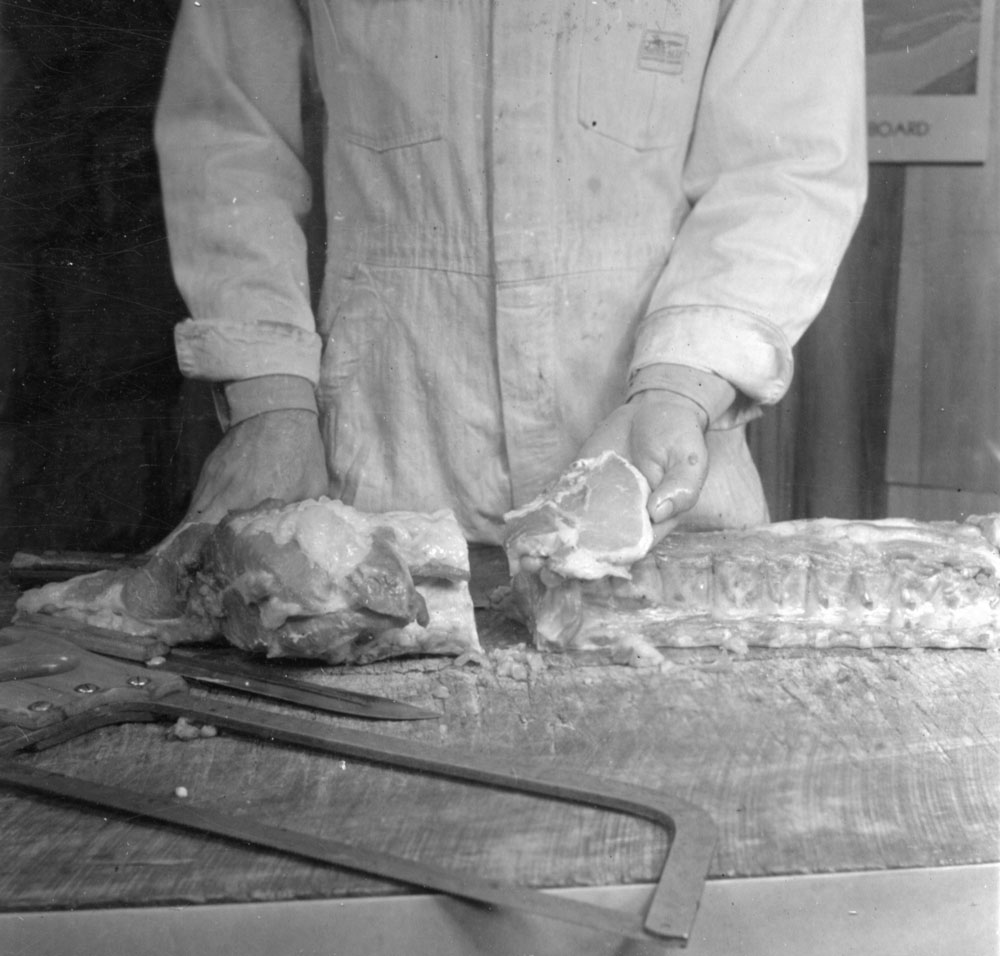

Classroom instruction. Butchering meat.[harm_088]

While Morris prepared extensive reports for the Board of Trustees on the intellectual life of the students and the productivity of the staff, he never failed to integrate the educational value of the farm and the importance of this program to the institution. The farmer was included in classroom instruction and integration of current trades related to the farm were explored such as butchering, farmer’s cooperatives, poultry farming, dairying, etc..

APPRAISAL – COMING AND GOING

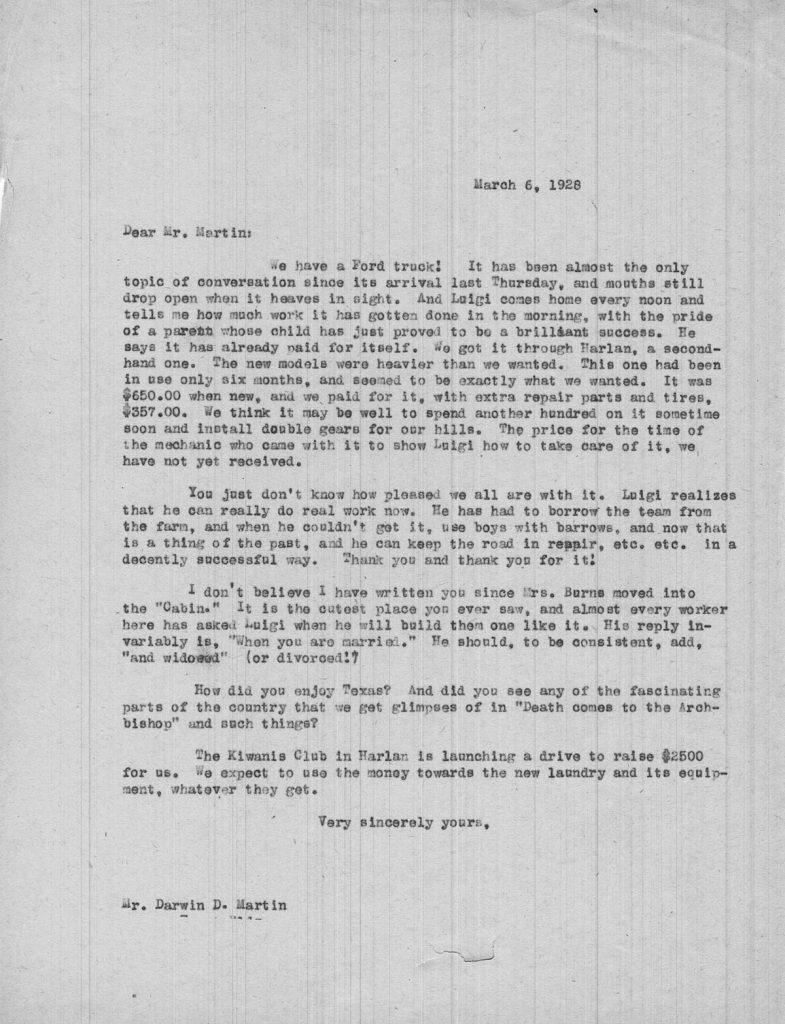

Morris’ farm-focus is found in his first bulletin addressed to the Board in December of 1931. It reflects his close attention to detail and his hands-on approach to all activities of farm-life at the School.

“Since the meeting of the Board here, we have acquired four shoats from Mr. Kenneth Nolan, as payment for the children’s tuition here at school. This addition gives us a total of six hogs, two large and four small. We have about completed the construction of a modern hog house, design as recommended by the Extension Department Department of Agriculture, University of Kentucky. This house is so constructed as to give the maximum of air and sunshine. It has a concrete floor which can be washed as often as desired. This will mean that we will keep our hogs and their living quarters as clean as possible. This project serves a two-fold purpose: that of raising some of our own meat, and as a demonstration of how hogs should be kept.

Another project which we are about to enter upon is that of remodeling our manure pit, which is at present very impracticable. We are going to cut down some of the wall and add a liquid manure cistern, also construct a roof over the manure pit. At current prices, our manure as fertilizer is worth over one thousand dollars a year, but if it is not kept in a manure pit, 50-5% of its value is wasted by being exposed to the elements. Manure is a an almost perfect fertilizer, with the exception that in this section of the country we need more phosphorus. With proper care, our solid and liquid manure should prove a more valuable asset than it has in the past.

We are pleased to announce that yesterday one of our cows, Lucy, gave fifty -two pounds of milk (twenty-six)quarts). At the present time the cows are giving more milk than we can consume in liquid form, and we are making the surplus into butter. ”

Over the course of his tenure at the School farm-life in the country underwent a major shift as industrialization began to dominate farming throughout the country and as the realities of weather, drought, floods and other adversarial events eroded the farm program. In his 1937-1938 Annual Report to the Board of Trustees , just before leaving the school to join the war effort as a Chaplain in the Army, Morris described a recent assessment of the farm activity:

“A critical appraisal of crops for the past year is not encouraging. The dairy continues to profit from the farm, but in the main the quantity of produce raised on the farm for school consumption during the winter was not sufficient to warrant the expenditure and effort involved. Sufficient beans were canned to last all year — and sufficient potatoes grown, but other crops were not successful. Approximately twenty acres are under cultivation. The school possesses at the present time fourteen cows, two heifers, three calves, one bull, one hundred twenty-eight hens, and seven pigs.”

In the 1936-37 years the financial statement of the school aggregated the farm under “Living” which included the subheadings of Salaries, Provisions, Dairy, Farm and Garden, Poultry, Kitchen, and Dining Room. The total expense of this aggregate for the year was $15,683.68. The expenses associated with the educational programs were $8,324.05. These comparative figures suggest that “Living” was starting to pull substantial revenue from the educational programs side. Educational costs were listed as: Academic salaries and supplies; Domestic Science [Country Cottage] ; woodworking ; weaving ; printing ; automotive. Administrative expenses were totaled at $5,708.58 and included the Director’s salary and travel expenses ; Office ; Endowment Fund [management] expenses ; and Publicity. Morris was a farmer, but he was first an educator.

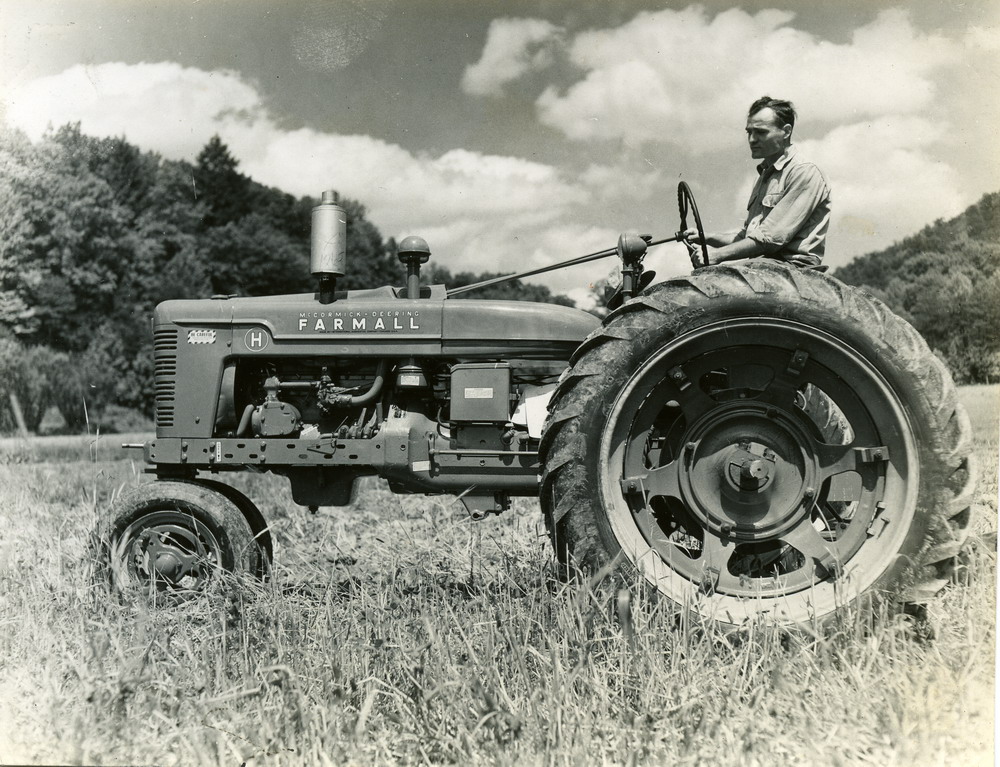

William Hayes on new Farmall Tractor at PMSS, c. 1943.

Also, somewhere in the later reports was the purchase of a new Farmall tractor in 1946. The old Ford tractor had been patched up for the last time and the many tasks of cultivating the land could not revert to horse and plow. The new tractor was expensive but vital to the continuation of farming at the school. It unfortunately came too late to save the future of farming at the school and in the region, though it was intended to off-set the intense human labor needed to maintain a growing farm. While new developments in technology aided the farmer significantly, much of the new equipment and technology was beyond the finances of the small farmer. Small farms were slowly being eliminated as market forces, began to argue for farm conglomerates and mechanization of many farm tasks. Pine Mountain had no immunity to this national shift.

Though efforts were made to introduce new technologies into farming practice, all signs pointed to the closure of small-scale farming across the country. The farm and the Ayrshire dairy programs continued for a brief time but the farming model was changing to the larger agri-farm model. Educational models were also rapidly changing and the closure of the boarding school program in 1949 ended the student labor program and consequently the dairy labor force. This reduction in available labor was a strong indication that the program could not survive. Further, the consolidation of the school with Harlan County Schools precluded the need for production of milk for the resident student population and signaled a new standardized educational curriculum. The herd of cows was finally sold in 1952. All these change agents forced the closure of the dairy farm as central program at the School in that year.

New regulations and increasing costs added to the woes of not just PIne Mountain, but to all small farms and farmers throughout the region during this period. The dairy operation had no choice but to shut down as it was no longer economical to continue production of milk for sale as the new regulations, increased competition, and other regulatory restraints, made production of milk for sale very difficult and expensive for farms the size of Pine Mountain. In 1920 there were no dairies in Harlan County. In 1924 there were 24, but by the 1940’s the number of dairies was radically cut and milk supplied to local facilities such as Chappell’s Dairy, was largely supplied by farms outside the county. The eras of agri-business were just emerging throughout the country and the shift in the family farm was rapidly changing how farming would persist over the next many eras.

By 1955 not only the dairy, but small farming, generally, at Pine Mountain was perceived to have run its course. The farmer, William Hayes, had left for other employment, the silo was sold, the need for silage no longer existed, and the farm machinery was idled for lack of able labor to run and to repair it. Pieces of equipment were slowly sold or discarded as the tools for farming and for the dairy fell into disrepair. By 1955, the barn was largely empty except for storage of school lumber and some machinery. Some of the more remote fields had started to fill with the early saplings of a forest as many fields always in production and long tilled, had not seen a plough for years. The so-called Deschamps field, above Old Log and the field below the old CCC cabin, behind Burkham School House II, were the first to be consumed by forest. Later, the field beside Practice House (Country Cottage) was let go and it quickly filled with saplings as the forest reclaimed its hillsides.

Today there are only a few signs of the early and robust farm and many of the fields that supported those efforts. The farming that won accolades for conservation and productivity can not easily be discerned in the surroundings. Today, only the stone walls of the milk-shed , its roof long ago fallen-in, may be found next to the barn, as an architectural reminder of the milk production years and the tool shed equipment rooms changed from farm equipment to lawn mowers and weed-eaters, and sporadic gardening.

DOCUMENTATION

The documentation of the history of the dairy farm is a rich collection at Pine Mountain. The documents give a graphic picture of the decisions made regarding the farm but the photographic history, also a form of documentation, is more difficult to read. For example the “Master Pastureman” awards and long lists of milk production and quaint names of cows and the even more quaint and delightful letters and diaries of Elizabeth Hench, tell the dairy story in pictures, but to get the full story they must combine with the later documents. The archives tell the story of the early era of dairy management at the school and the bounty of the fields in production. Each year the annual reports and the bi-annual board reports followed the farming practices of the School. Maps, photographs and other media also capture the visual changes that accompanied the evolving story of farming at Pine Mountain School. Snippets of stories from students and staff who worked in the dairy and on the farm appear in the school newsletters and in personal recollections and letters and can be mapped to photographic material forming a richly documented history of small-scale farming.

For those interested in the evolution of subsistence farming, the Pine Mountain collections provide a rich body of research material. This blog is but one perspective gleaned from the records.

Overall, the closure of the Pine Mountain School dairy and the farm presents as a financially pragmatic action. It was consistent with the rapid changes occurring throughout small farms in Appalachia following WWII. As farmers struggled to re-position themselves in the new economy and the rapid development of mega-food supply chains, many farmers reverted to subsistence farming and became miners to supplement their income. Transport and distribution became a topic of great concern across the country and though roads now penetrated the valley of Pine Mountain, the distance and time to market was considerable. Further, the closure Pine Mountain’s functional farm was directly tied to the closure of the boarding school, its training programs.The collapse of the ready supply of labor was a significant loss and played a major role in the demise of concentrated farming at the settlement school.

Even robust programs such as the McClure’s popular Farmer’s Federation cooperative in western North Carolina near Asheville, encountered increasing pressures from transport to distribution. Most other settlement schools and mission schools that had supported farms had already either closed or had found new directions that did not include farming practice. There were remarkable exceptions to these farm closures such as the Farm School, now Warren Wilson College in North Carolina, which persisted and continues in an amended educational form, today. And, to a limited extent, the farm at John C. Campbell Folk School, also in western North Carolina continued its farm program. The Berry School in Georgia has maintained a farming presence through to the present day, in part due to the large land-holdings of the institution.

Many of the settlement institutions with functioning farms found ways to fiscally incorporate their farms into the educational process, such as work-study programs, or community programming, or agricultural courses but most had a continuous and ready supply of labor. These examples speak to the sustainable and current remarkable resurgence of the farm in many educational milieus. This is particularly seen in the developing “Farm to Table” programs and the “Grow Appalachia” programs at Berea College, which now partners with Pine Mountain Settlement School. Finding new pathways to incorporate farming into the new programs at Pine Mountain is ongoing and the future looks promising for a strong resurgence. But, that is another long and promising story.

GO TO:

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH – ABOUT

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH I – GUIDE

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH II – INTRODUCTION

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH III – Place

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH IV Farming the Land 1913-1930

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH V Farm & Dairy I Early Years

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH V Farm & Dairy II Morris Years

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH VI Poultry

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH VII In the Garden

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH VIII In the Kitchen Pots and Pans

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH IX Dieticians

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH X In the Dining Room, Manners & Etiquette

![Boy's House Wassailers and Lords and Ladies -- 1946. [Good King Wenselaus ?] [In Laurel House] nace_1_025b.jpg](http://staging.pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/nace_1_025b-1024x573.jpg)

![Angela Melville Album II - Part III. "E.K.W." [with dulcimer]. [melv_II_album_313.jpg]](http://staging.pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/melv_II_album_313-194x300.jpg)